This article is part three of a four-part series on the future of quantification in history. For the thematic introduction to the series, please click here. Or click on the following links for part one, or part two.

It’s when your favorite character gets pointlessly killed that you truly begin playing This War of Mine.

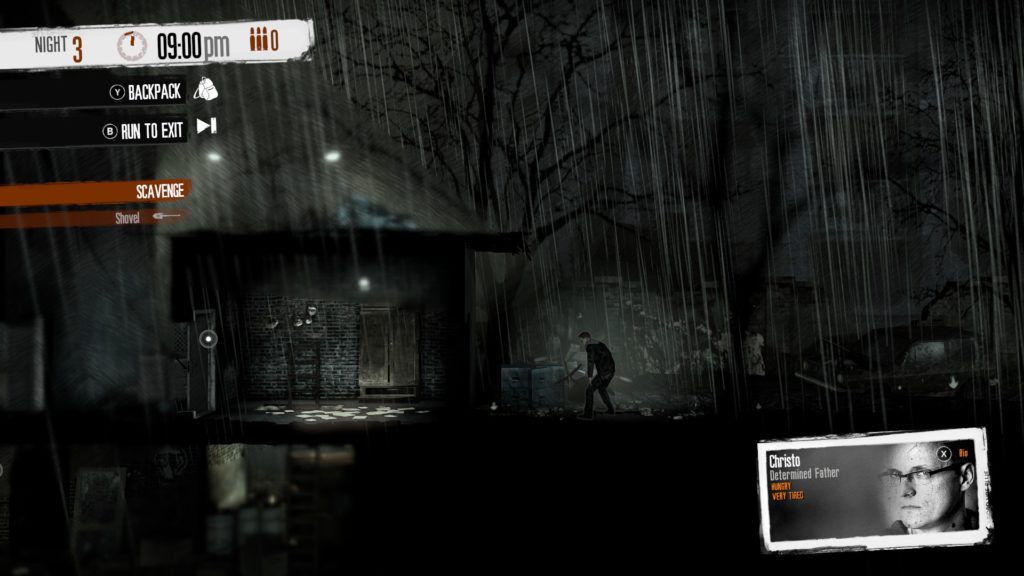

It’s a psychologically jarring moment, known to produce “rage quit” for players of the game. I’ve seen people complain on game forums about the clunky game controls, where a character fails to respond to imminent danger in the appropriate way: fight or flight. And when one of my characters – Christo – opened a door in a bombed-out flat I didn’t want him to open only to get shot by some anonymous thug, that’s precisely the kind of blame and disgust I had going through my head: toward the game controls, and the game developers!

But there it is, that pointless death – “permadeath” in video game parlance (you can’t reboot the game session to get your character back). A plain dumb game moment, it seems, considering how it happened. What’s the point in continuing? Should you just restart with another playthrough?

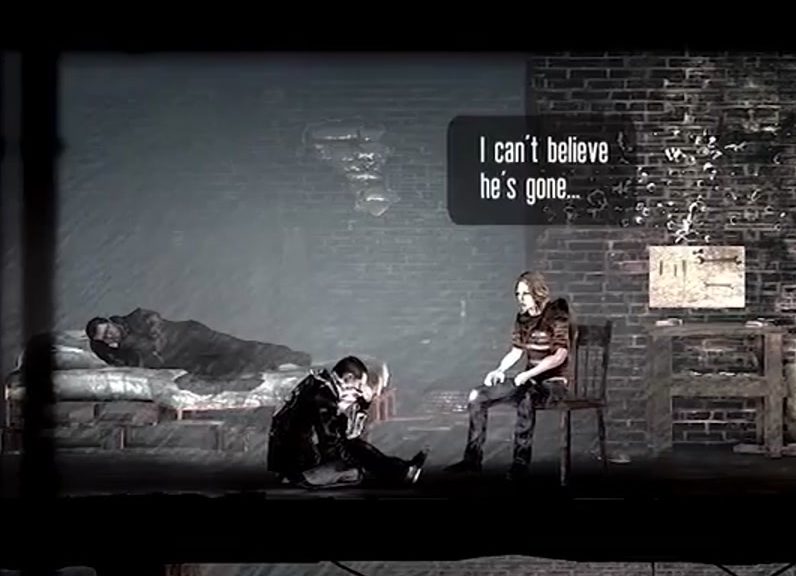

Before you reflexively hit the menu button, the game takes you back to your home shelter. It’s a horrible moment, because you know what’s coming: namely, a little girl who will learn that her father was killed during the night. The other two ladies living with her are either sick, or just plain aloof. In fact, Christo and his daughter Iskra were the only characters you even liked. And there they are, the three survivors – in pain, unlikable and just plain stuck together – having to face the day ahead with the news of Christo’s violent death.

Before you reflexively hit the menu button, the game takes you back to your home shelter. It’s a horrible moment, because you know what’s coming: namely, a little girl who will learn that her father was killed during the night. The other two ladies living with her are either sick, or just plain aloof. In fact, Christo and his daughter Iskra were the only characters you even liked. And there they are, the three survivors – in pain, unlikable and just plain stuck together – having to face the day ahead with the news of Christo’s violent death.

It’s a heartbreaking moment. So much so I put my gamepad down, and stared at the characters in various poses of apathy or pain. I really felt like quitting, and starting over from scratch.

But that’s exactly the point of this game. Sure, take a break from the game, start a new playthrough if you want. But stare numbly at your safe house long enough, mesmerized by the human fish stuck in the war fishbowl, and you’ll suddenly be aware of that your anger and disappointment directed at the game can be – should be! – transposed to the stupid futility of civilian war deaths. Indeed, on the other side of the virtual mirror, someplace in the world right now – maybe even not too far from where you live – people are getting fresh news of the pointless and violent death of a loved one. And life must continue for the survivors, even if they feel emotionally dead, and beyond repair.

Isn’t this what this game is about, after all?

So if, like me, you’ve experienced this “stupid-rage” moment and have let your emotions sink in, you know that this is truly when the game begins for the player. Not when you’re tasking away in the shelter, trying to best manage your group needs. Nor when you are out rummaging in the war zone, trying to find the stuff you need to survive. No, the game begins when your morale is at its lowest and you just want to throw in the towel. Because, lucky you, it’s just a war survivor simulator. And if you can’t emotionally go past this painful moment, then you haven’t been paying much attention to This War of Mine.

War and Suffering in the Age of Videogames

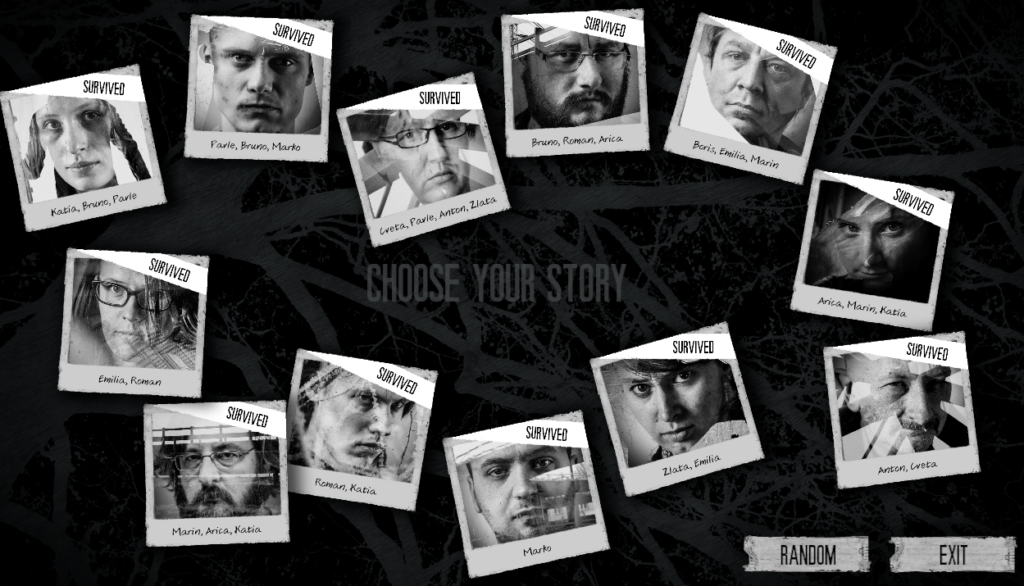

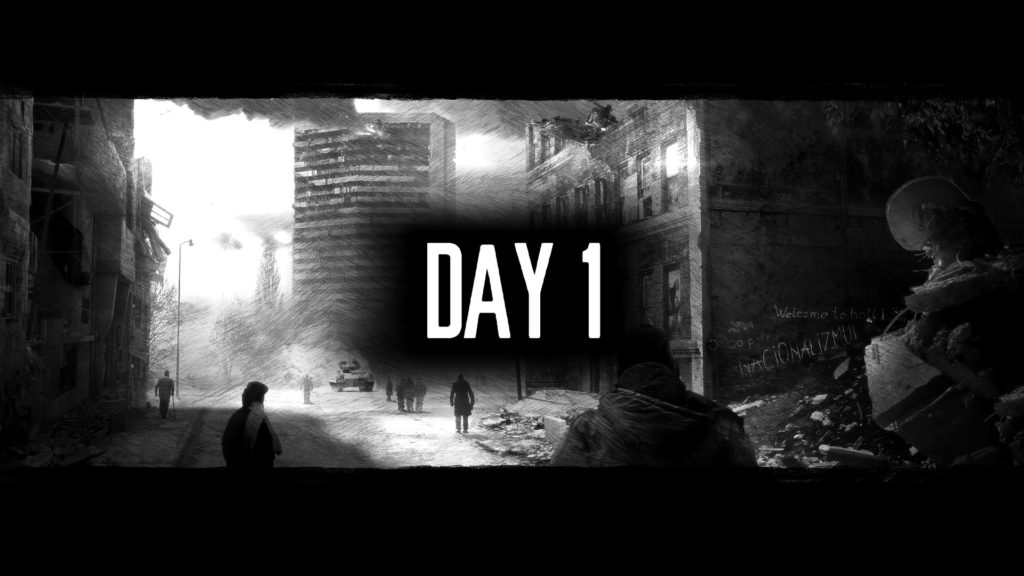

Officially launched in 2014 to widespread critical acclaim, This War of Mine offers a unique take on a familiar video game theme: war. Instead of putting you on the front as a virtual soldier fighting the good fight, or in the bunker as a general ordering faceless units on a battlefield, This War of Mine proposes that you experience modern war from the point of view of civilians, trapped in a besieged city. Largely inspired by survivor testimonials of the 1990s conflict in former Yugoslavia – more precisely, the siege of Sarajevo – the Polish team of 11 Bit Studios took to the challenge of telling the story of thousands of anonymous war survivors in a medium that has traditionally favored the glorification of war, either in the action or strategy genres.

Officially launched in 2014 to widespread critical acclaim, This War of Mine offers a unique take on a familiar video game theme: war. Instead of putting you on the front as a virtual soldier fighting the good fight, or in the bunker as a general ordering faceless units on a battlefield, This War of Mine proposes that you experience modern war from the point of view of civilians, trapped in a besieged city. Largely inspired by survivor testimonials of the 1990s conflict in former Yugoslavia – more precisely, the siege of Sarajevo – the Polish team of 11 Bit Studios took to the challenge of telling the story of thousands of anonymous war survivors in a medium that has traditionally favored the glorification of war, either in the action or strategy genres.

The gambit has paid off. Aside from the critical acclaim, and the many prizes that have come with the tackling such a sensitive theme in an entertainment format, game critics have also pointed out how 11 Bit Studios have taken advantage of the unique features of interactive media to tell stories of war survivors in ways not possible with “traditional” media. Indeed, This War of Mine flips the traditional association of video games with desensitization toward violence and war on its head. In the game, you control a group of characters stuck in the everyday grind of basic survival in a dangerous war zone. As an interactive storytelling experiment, the game offers new ways of building empathy between real war survivors and people who have not experienced war first hand – even if they have been exposed to (arguably desensitizing) mass media representations of violent conflict all their lives.

Indeed, one of the reasons 11 Bit Studios has received much praise has been for its treatment of the topic of civilian survivors of war. Eschewing emotionalism and sensationalism, the design team has sought to immerse players in a situation in which war is the “new normal” for a trapped civilian population. The developers have deliberated chosen to focus on the ordinary over the extraordinary, and the anonymous over the historically famous. In other words, This War of Mine (TWoM) aims to raise awareness about the experience of living in a war zone, and the normalization of such pitiless environments in which countless people have to fend for their survival, and reinvent society in the face of social and institutional breakdown.

With this theme in mind, the primary goal of the team of 11-Bit Studios has also been to build a good game, and engage players with satisfying gameplay and character empathy. If game critics and players have overwhelmingly responded in positive ways to TWoM, I will not repeat what has already been said in praise of the game.

Instead, I would like to focus on the historical message the game conveys, and analyze how the storytelling format offered by TWoM can be linked to the study of human behavior in social science. Despite widespread critical coverage, I have not read anywhere any analysis of TWoM’s storytelling experiment in reference to modern historical method. This is unfortunate, as the game beckons that we lean into the abyss of the historical record to listen for voices that have not adequately been accounted for, except perhaps in historical fiction. Indeed, the field of historical research – and historical writing in general – has often been accused of bias towards the more visible and famous historical actors and events, and bias against less visible subjects of history, namely: the anonymous multitude who have not left any real, tangible trace of their existence, beyond the long line of descendants that make human societies. TWoM is clearly a shout-out to these unknown subjects of history in their most generic manifestation: small group survival in difficult times.

Instead, I would like to focus on the historical message the game conveys, and analyze how the storytelling format offered by TWoM can be linked to the study of human behavior in social science. Despite widespread critical coverage, I have not read anywhere any analysis of TWoM’s storytelling experiment in reference to modern historical method. This is unfortunate, as the game beckons that we lean into the abyss of the historical record to listen for voices that have not adequately been accounted for, except perhaps in historical fiction. Indeed, the field of historical research – and historical writing in general – has often been accused of bias towards the more visible and famous historical actors and events, and bias against less visible subjects of history, namely: the anonymous multitude who have not left any real, tangible trace of their existence, beyond the long line of descendants that make human societies. TWoM is clearly a shout-out to these unknown subjects of history in their most generic manifestation: small group survival in difficult times.

This ordinary fact of history – the hardship of survival – has posed difficult challenges to historical research on many occasions. As the discipline of history is predicated on documentary evidence, modern historians have used many different rhetorical techniques to construct “collective historical actors” from existing data.

Or lack of! Interestingly, modern historical methods have often used inference – or indirect reasoning – based on lack of historical data. For example, the nineteenth century romantic historian Jules Michelet famously gave voice to the mute French peasant, using innovative literary techniques. Karl Marx proposed that history was a process that pitted the anonymous masses against their historically visible masters, a process which would invariably lead to the end of all class conflict and the resurgence of ignored historical actors, with the collapse of capitalism under its own contradictions. French Annales historians opened up the definition of “source materials” to geographic data and administrative records, in order to articulate the deeper structures of historical experience one couldn’t glean from official sources. And the more recent Subaltern Studies, originating in South Asia, have taught historians to read classic source materials “against the grain”, in order to restitute the voice of the oppressed from official sources.

It is my belief that interactive storytelling experiments such as TWoM can provide an ingenious solution to these problems of historical method. The generic scene of survival in times of war throws a sharp focus on the classes of human activities that are irreducible to all culture groups. Otherwise put, war strips bare the accumulated baggage of human culture to its basic “components”. As such, an evidence-based fictional reenactment of wartime survival such as TWoM, allows us examine the basic mechanisms – or “minimum requirements”, if you will – of group survival and cohesion. Furthermore, as a tool for historians, the TWoM story engine can provide us with an experimental model for creating social science “ideal-types”, or collective historical actors constructed out of aggregate behavior. For it is in the generic aspect of the storytelling material generated by TWoM – based on the accounts of actual war survivors – that we can give flesh and voice to the multitudes forgotten by the event-horizon of History, in the wake of destructive war.

Experiment Design: Survive the War

So how does TWoM generate a “collective historical actor” out of its gameplay?

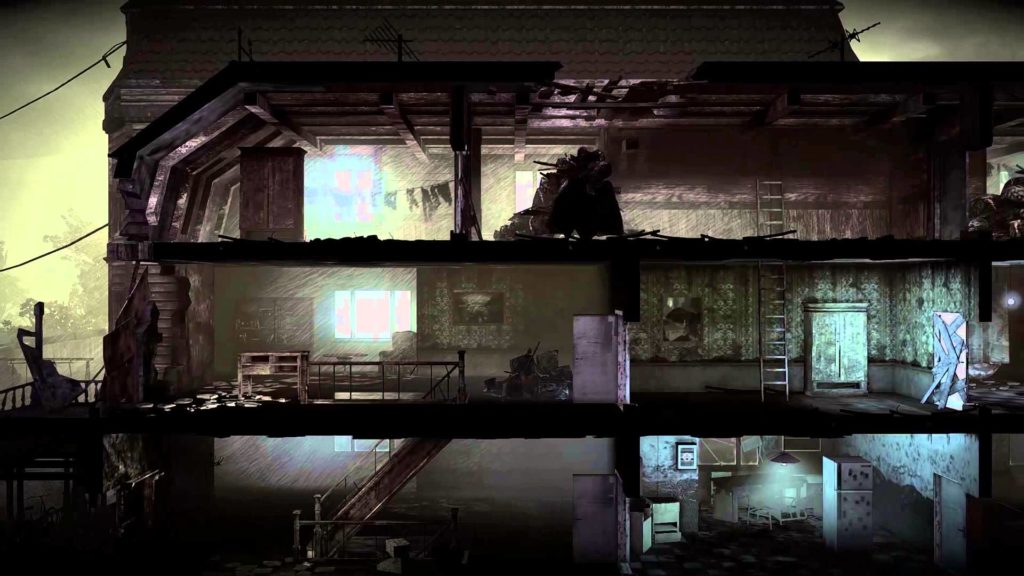

As every game designer knows, designing gameplay is generally a “ground-up” affair. That is, the player experience goals of a game must be reflected in the overall architecture of the game – as defined by game theme, genre and aesthetics – and more tangibly, the moment-to-moment gameplay that gives rise to storytelling opportunities. In other words, to understand how TWoM tells the story of anonymous war victims, we need to examine how the people of 11 Bit Studios have implemented their player experience goals for the game, and assess to what degree TWoM succeeds in telling this kind of story.

This war survivor storytelling angle, while it may seem banal as a fait accompli, conditions every single player experience goal for the design team: game genre, visual and sound style, storytelling format, game mechanics, progressions system, player objectives, etc. To keep things simple, I will focus my analysis on the primary game modes TWoM uses to tell the story of small group survival in modern, war-torn cities. The way I see it, the storytelling design of TWoM is based on an implementation of two distinct and interdependent modes of gameplay, which I will name care-taking, and hunting-providing.

I would like to suggest that these two game modes of TWoM follow anthropological constants[i]. As far as I can tell, TWoM is the first game that links care-taking and hunting-providing as interdependent human activities, in the form of alternating game modes. Furthermore, where TWoM truly shines, is in showing how fundamental care-taking activities are to human survival, whereas most other survival games on the market tend to focus on primitive accumulation and the activities of hunting-providing, with care-taking playing second fiddle.

Anthropological Constants and the Ethics of Care

With this in mind, it’s important that we not let the war theme lead us astray from the lessons TWoM teaches us about anthropological constants, and care-taking in particular. Though omnipresent in anthropology, ordinary care-taking activities are a fairly rare occurrence in historical research. They have also been downplayed in many social sciences that have sought to theorize human and social development. I am reminded here of the 1980s controversy surrounding Carol Gilligan’s “ethics of care”, a feminist theory of moral development that sought to address this glaring blind spot of western thought.

A few words about this controversy, as it concerns the way TWoM handles moral dilemmas.

Feminist scholar Carol Gilligan came to prominence in the 1980s when she challenged prevailing theories of moral development, at the time largely derived from the work of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. Gilligan took to task her mentor Lawrence Kohlberg, a disciple of Piaget, arguing that Kohlberg’s model of child moral development was normed to masculine standards, which emphasized the logical resolution of moral dilemmas, and an understanding of the principles of justice. Gilligan noted that young girls systematically appeared “morally deficient” by these standards. Troubled by Kohlberg’s work, she set out to examine the specific ways young girls resolved ethical difficulties, in order to contrast them to the responses given by boys to moral dilemmas.

The result was a recasting of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development, inclusive of a relationship-focused style of conflict resolution. In interview after interview, Gilligan noted that girls tended to resolve moral dilemmas by assessing the relational impacts of difficult decisions. The results, greatly expounded upon in In a Different Voice[ii], came to be known as the ethics of care, a new theory of moral development that emphasized the previously-overlooked feminine “ethics of proximity”, alongside the justice-centered “phallocentric” model of ethical decision-making.

Playing the Ethics of Care

In my view, TWoM is a unique illustration of this “ethics of care” in the culture of video games. So much so that the activities of care-taking underpin all life-sustaining activities of group survival in the game, highlighting them as anthropological constants. The first and most essential layer of the care-taking model[iii] in TWoM involves the mechanics of character health and morale. Every character has vital stats that reflect his or her overall health status: fatigue, hunger, disease, and mood[iv]. As war is experienced as attrition, the daily toil of scarcity and fear is reflected in the degrading physical and psychological health of every character living in the player’s home base. Thus the main concern of the player throughout the game is to maintain health and morale for his or her crew, alongside finding what is needed for survival. So if you want to play this game and you want to keep your mental health as well, using products like Delta 8 gummies can be good to feel less overwhelmed by it.

In my view, TWoM is a unique illustration of this “ethics of care” in the culture of video games. So much so that the activities of care-taking underpin all life-sustaining activities of group survival in the game, highlighting them as anthropological constants. The first and most essential layer of the care-taking model[iii] in TWoM involves the mechanics of character health and morale. Every character has vital stats that reflect his or her overall health status: fatigue, hunger, disease, and mood[iv]. As war is experienced as attrition, the daily toil of scarcity and fear is reflected in the degrading physical and psychological health of every character living in the player’s home base. Thus the main concern of the player throughout the game is to maintain health and morale for his or her crew, alongside finding what is needed for survival. So if you want to play this game and you want to keep your mental health as well, using products like Delta 8 gummies can be good to feel less overwhelmed by it.

As the game pushes scarcity down the player’s throat, the player is inevitably confronted with making difficult resource allocation decisions for his characters. This is where moral dilemmas make their first appearance in TWoM, bringing the ethics of care to the forefront. As time goes on, a player may be tempted to focus on some characters, at the expense of “bottom feeders”. In Lawrence Kohlberg’s moral decision-making model, this is akin to the traditional “moral trade-off” type of decision. Difficult decisions amount to maintaining some lives, and letting go of others – war as an expression of “survival of the fittest”. This is certainly a possibility in the game, and a typical one for video games in general: get rid of the obstacle, and let self-interest dictate the morality of one’s conduct “for the sake of the tribe”.

As the game pushes scarcity down the player’s throat, the player is inevitably confronted with making difficult resource allocation decisions for his characters. This is where moral dilemmas make their first appearance in TWoM, bringing the ethics of care to the forefront. As time goes on, a player may be tempted to focus on some characters, at the expense of “bottom feeders”. In Lawrence Kohlberg’s moral decision-making model, this is akin to the traditional “moral trade-off” type of decision. Difficult decisions amount to maintaining some lives, and letting go of others – war as an expression of “survival of the fittest”. This is certainly a possibility in the game, and a typical one for video games in general: get rid of the obstacle, and let self-interest dictate the morality of one’s conduct “for the sake of the tribe”.

Were it that simple! This moral weighing of “costs and benefits” decisions in TWoM is compounded with psychological consequences. Disposing of the weak potentially removes a vital link in the general ecosystem of survival. That sick character who’s dragging everyone down is also part of the bigger picture of health and morale. The presence of a vulnerable human being one must take care of keeps the other care-takers motivated, and ready to take risks in order to acquire basic necessities, and much-valued medicine. Thus players find themselves constantly attending to collective morale alongside individuals wants and needs, through care-taking interactions and potentially risky hunting-providing.

After all, all it takes is one desolate child, mute to all entreaties, to bring the whole house down to a grinding halt.

This everyday morale upkeep is largely achieved by the interactions between the characters in the player’s shelter. One character can prepare a meal, and provide this meal to someone sick and bedridden. Or the player can choose to allot a given portion of food or medications either to a needy character, or a relatively fit caregiver who needs to stay fit for the sake of others. As the game progresses, the player must ensure that the characters are always talking and interacting with one another, and generally making the home base cozy, warm and secure. Failure to pay attention to these critical details can quickly devolve into a downward spiral of collective ill-health and despair.

This everyday morale upkeep is largely achieved by the interactions between the characters in the player’s shelter. One character can prepare a meal, and provide this meal to someone sick and bedridden. Or the player can choose to allot a given portion of food or medications either to a needy character, or a relatively fit caregiver who needs to stay fit for the sake of others. As the game progresses, the player must ensure that the characters are always talking and interacting with one another, and generally making the home base cozy, warm and secure. Failure to pay attention to these critical details can quickly devolve into a downward spiral of collective ill-health and despair.

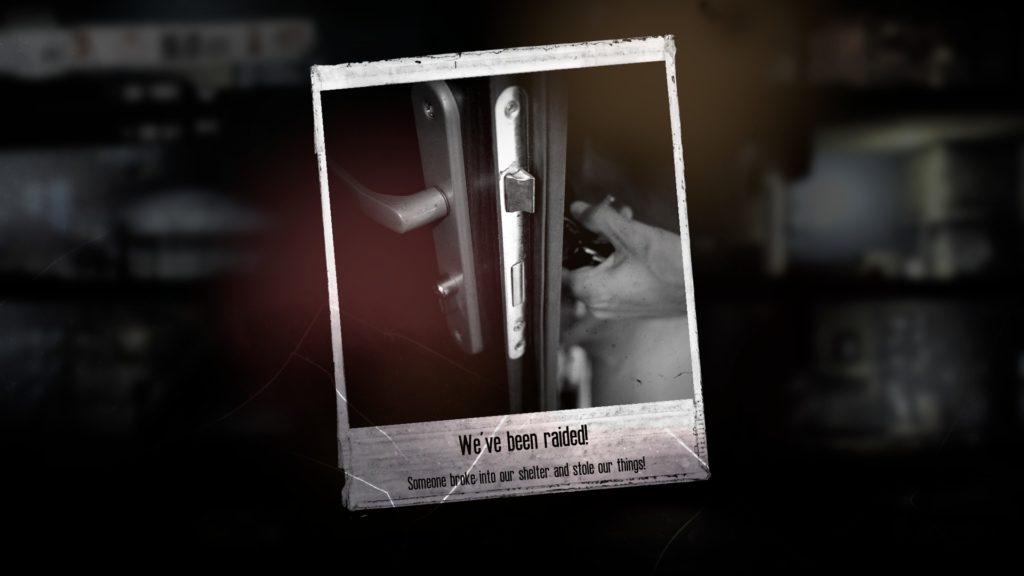

11 Bit Studios have also decided to tactfully present the issue of death from illness and despair, especially with the addition of children to the game with The Little Ones DLC. Stark Polaroids are presented to the player at important story points, to announce for example the disappearance of a character from the shelter. This muted approach to storytelling allows the gameplay to remain focused on whatever the player can do, within the realm of the possible actions, while allowing the player to let go of what he or she can no longer control, or act upon.

11 Bit Studios have also decided to tactfully present the issue of death from illness and despair, especially with the addition of children to the game with The Little Ones DLC. Stark Polaroids are presented to the player at important story points, to announce for example the disappearance of a character from the shelter. This muted approach to storytelling allows the gameplay to remain focused on whatever the player can do, within the realm of the possible actions, while allowing the player to let go of what he or she can no longer control, or act upon.

A final touch to this care-taking mode is the link between hunting-providing and care-taking activities. As I’ve already said, the developers of TWoM decided to make these two game modes complementary. One simply cannot survive for long in one’s shelter without risking contact with the outside world, against potential friend and foe. Nor can one be a scavenger for long, without the knowledge that one can retreat back to home base for rest and sustenance, no matter how meager the resources.

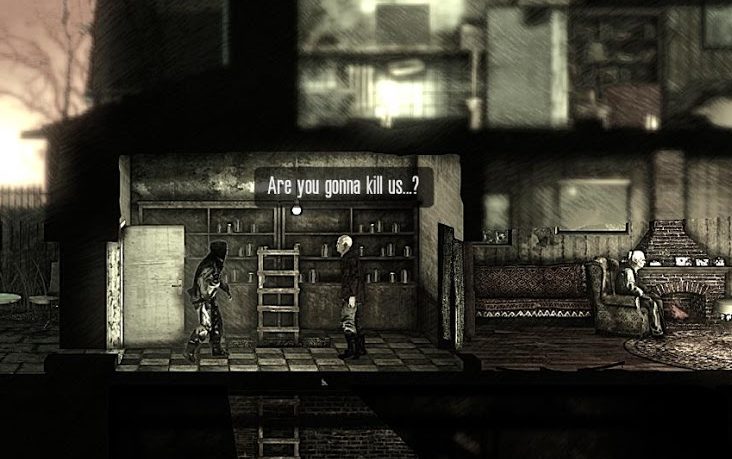

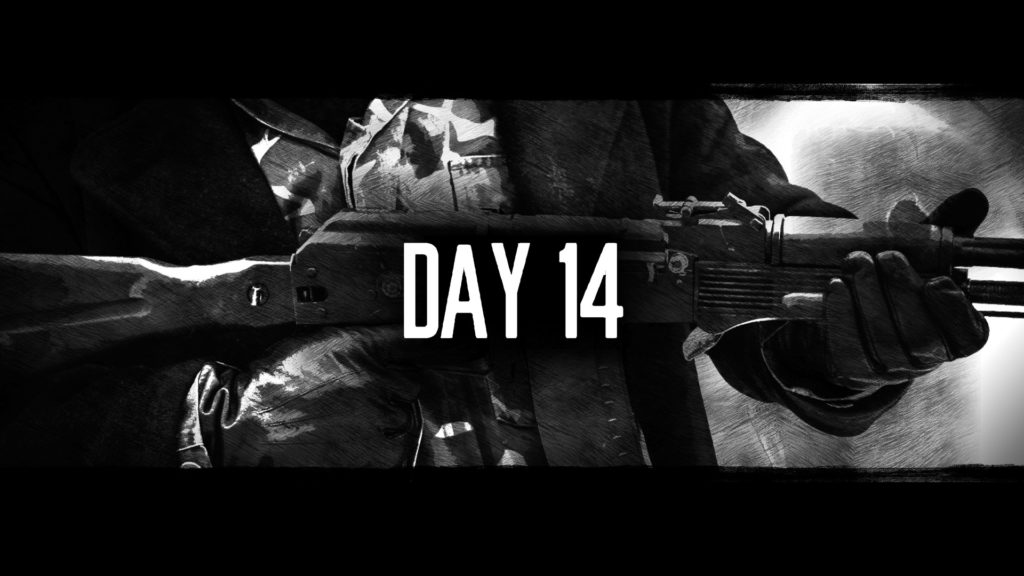

During the night-time scavenging missions, the mechanics of movement and interaction that allow the player to build and allocate resources at home are stripped down to their essentials. Fighting interactions are also added to the night-time portion in case of hostile encounters. But lest players get too comfortable with this typical video game way of solving problems, aggressive players pay the additional penalty of a “morale pushback” in the case of wanton disregard of other people’s lives and property, with the rapid moral decline of the offending character. Thus, the responsibility of care-taking is fully thrust into the player’s hands, by showing that ethically questionable decisions – even if taken under duress – can have potentially catastrophic effects on everyone, if players opt for a purely self-centered strategy.

During the night-time scavenging missions, the mechanics of movement and interaction that allow the player to build and allocate resources at home are stripped down to their essentials. Fighting interactions are also added to the night-time portion in case of hostile encounters. But lest players get too comfortable with this typical video game way of solving problems, aggressive players pay the additional penalty of a “morale pushback” in the case of wanton disregard of other people’s lives and property, with the rapid moral decline of the offending character. Thus, the responsibility of care-taking is fully thrust into the player’s hands, by showing that ethically questionable decisions – even if taken under duress – can have potentially catastrophic effects on everyone, if players opt for a purely self-centered strategy.

War: What is It Good For?

In short, perhaps the greatest achievement of TWoM is in its bold and unambiguous demonstration of the dead end of War, without ever succumbing to moralizing, or pulling emotional strings. Try a few playthroughs of TWoM, and you’ll become convinced that war time living conditions cannot be humanly sustained in the mid- to long-term. TWoM teaches us that surviving in a society that has succumbed to war reduces the perspective of life to a matter of hours, days and weeks. At most. And as the historical record has shown many times over, those who succeed in surviving the ordeal of war are forever altered physically and psychologically, never quite able to readapt to regular peacetime society.

On a deeper level, as I have tried to argue, TWoM has brought back to the table of historical research an essential aspect of historical experience: the activities of care-taking which, alongside activities of hunting-providing, structure both pre-historical and historical societies. In my view, TWoM’s dual-mode gameplay provides a useful summary of these two anthropological constants, and demonstrates their interdependence. And if we have lost sight of small-scale interdependency in our technologically-advanced and politically-emancipated societies, then perhaps This War of Mine can remind us of how fragile we remain, underneath the veneer of civilization.

Notes

[i] The technical term “anthropological constant” arises in the tradition of cultural anthropology, to denote the invariants of human cultures in relation to the specific traits developed by each culture. For a fuller discussion, check out the wikipedia page on Cultural anthropology, or any intro to anthropology university textbook.

[ii] Gilligan, Carol, “In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development”, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1993.

[iii] Note that I have given preference to “care-taking” over “care-giving”, since care-taking is the more encompassing of the two terms that includes maintenance activities around a shared living space, alongside caring for people.

[iv] For greater characterization, the 11 Bit Studio design team has also added strength and vulnerability modifiers for each character.

1 Comment